It is not surprising, therefore, that rather than a one-off experiment from a first-time novelist, later novels continue to explore supernatural elements as potential solutions. Later in life she looked to shift the boundaries of this either–or gender dichotomy by referring to herself as ‘neither a girl nor a boy but a disembodied spirit’ suggesting that it is only disembodiment that can facilitate the escape from being read in relation to gender Forster, Daphne du Maurier, pp. Forster explains that early in life she comes to understand that ‘there was no escape from being a girl’ and so she must suppress the boy-in-the-box. The nature of the ‘solution’ made available to Janet is relevant to du Maurier’s own experience of gender where, at different times in her life she both came to understand the desire to escape her gender and the impossibility of that escape. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves. These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors.

The Cornish coastal site can be understood as both suggesting and denying freedom from gender within the context of its ambiguous relationship to England.

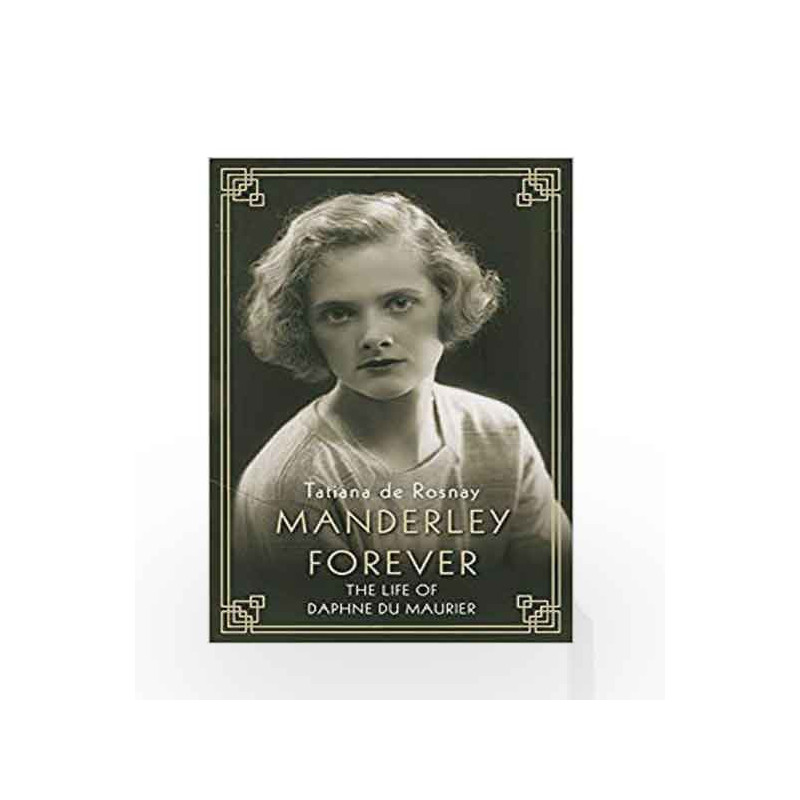

Janet Coombe and Dona St Columb look to escape social constructions of gender and the sea functions as a space of possibility for such an escape. The chapter problematises constructions of the Cornish coast and of gender in the novels through exploring the experiences of the novels’ female protagonists. The marketisation of ‘du Maurier’s Cornwall’ by the tourist industry feeds both a version of Cornwall as romantic and picturesque, and the pigeonholing of du Maurier’s novels as over-simplistically romantic. Goodman examines two of Daphne du Maurier’s Cornish novels – The Loving Spirit and Frenchman’s Creek.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)